American Airlines is the world’s largest airline. With hundreds of destinations, roughly a thousand aircraft, over one hundred thousand employees, and millions of customers, American Airlines has to juggle almost unquantifiable challenges every day to safely provide service to their airline and cargo customers. American recently invited media to participate in an all-night lock-in at their Integrated Operations Center in Fort Worth, Texas, for an inside look at their overnight operations. In this multi-part series we’ll take an inside look at overnight operations at the world’s largest airline.

Part I: Executives detail investments in customer experience

Part II: Touring the IOC and Landing an A350

Part III: Overnight Maintenance, American’s DFW Virtual Tower, and Epic Plane Pictures

December 26, 2018, was a bit of an anomaly for American Airlines. A thunderstorm hit American’s biggest hub, DFW Airport. That wasn’t the unusual part, though. After that thunderstorm hit, another hit, then another, and, just when forecasters thought everything was clearing up, yet another line of storms hit the airport.

It was almost unheard of: 6 hours and 22 minutes of consecutive thunderstorms. There wasn’t much American could do; when lightning strikes within 5 miles of an airport in the past 15 minutes, ground crew are not allowed to be on the ramp. Planes were stuck on the ground in Dallas, flights were diverted, crew were in the wrong place and timing out, and customers weren’t having a great experience.

When it comes to air travel the situation above certainly isn’t a worst case scenario for an airline but it’s about as close as it gets without something tragic or terrible happening. American brought in a few different senior staff members to walk the assembled media through American’s IOC for an inside look, not only at how the airline handles problems, but also how it “wakes up” every morning. It’s not always about things going wrong, although that’s what gets the most media attention, it’s also about making sure the airline is ready to go every day, a complicated symphony involving maintenance, crew scheduling, customer service, weather, and corporate security teams.

Touring the heartbeat of American Airlines operations, the IOC

Frank Coppola, IOC director, an airline industry veteran of 30+ years, gave us a quick overview of the IOC and talked mainly about American’s “Right Start” flights. Right Start flights are American’s flights that depart between 5-9am, basically the first flights of the day for the airline at its hubs. There’s a tremendous focus on these types of flights (not just by American but by other airlines as well) on the first flights of the day because delays at the beginning of the day can cascade and lead to longer delays throughout the day.

We walked around the IOC, which was fairly quiet (a good sign, for sure) but still awash with activity. As Frank told us, literally everything runs through the IOC as the heart of American’s operations: load, maintenance, dispatch, flight planning, weather, customer service, crew scheduling, social media, and corporate security.

As you’ll recall from Part I, a few of the media personnel decided to don the pajama samples we received, which made for some great double-takes from the staff working the IOC that evening.

The main floor of the IOC is windowless and columnless, providing unfettered access across the floor when needed. It’s a bit of a maze but each area is labeled and there’s a lighting system to indicate when someone is on the phone without you having to ask them.

As we walked around the IOC we stopped by various desks for briefings from IOC staff about what they were covering that night. Of note was a weather analyst watching a storm system over the South Pacific, as it could possibly impact American’s flight from LAX to Sydney. The analyst described his process for evaluating a storm system and the potential impact of trying to divert around a storm system as large as the one we were looking at. He wasn’t sure if the storm would require rerouting the aircraft yet, as it was still hours away, but it was interesting to hear the mindset he had as he was doing his job, thinking not only of weather but fuel, flight planning, etc.

The bridge of the IOC is probably the most important bit of square footage across all of American Airlines. The IOC directors sit there along with critical staff to give them needed feedback when it matters most. The directors are there to ensure things run smoothly but also to deal with potential emergency situations. Frank told us an example of a sports team on an American flight. The initial call they received was that every member of the team was vomiting and sick on the aircraft. The IOC pulled critical staff together, along with medical advisors, to assess the situation, as the situation sounded serious. As the rest of the story came out, only two members of the team were ill and the decision was made to let the flight continue as scheduled. It might seem like much ado about nothing but, as Frank told us, they would much rather prepare for a very serious situation and be happy when it turns out less so than be caught off guard.

As we left the bridge, I saw a row of reading glasses on a cabinet and thought they’d make for a great picture. The IOC has the potential for being one of the most stressful environments imaginable, I think we were all thankful to see it a bit more relaxed.

How American fights back against turbulence

It’s simply a fact of life: if you’re on an aircraft which stays aloft by slicing through the air, you’re going to encounter turbulence. Here’s the thing, and it should be reassuring for any of you nervous flyers out there (including myself): the airframe is at absolutely no risk of harm from turbulence. Turbulence poses enormous issues, however, for passengers and, especially, flight crew. Countless flight attendants have been injured on the job from unexpected turbulence, in some extremes severely.

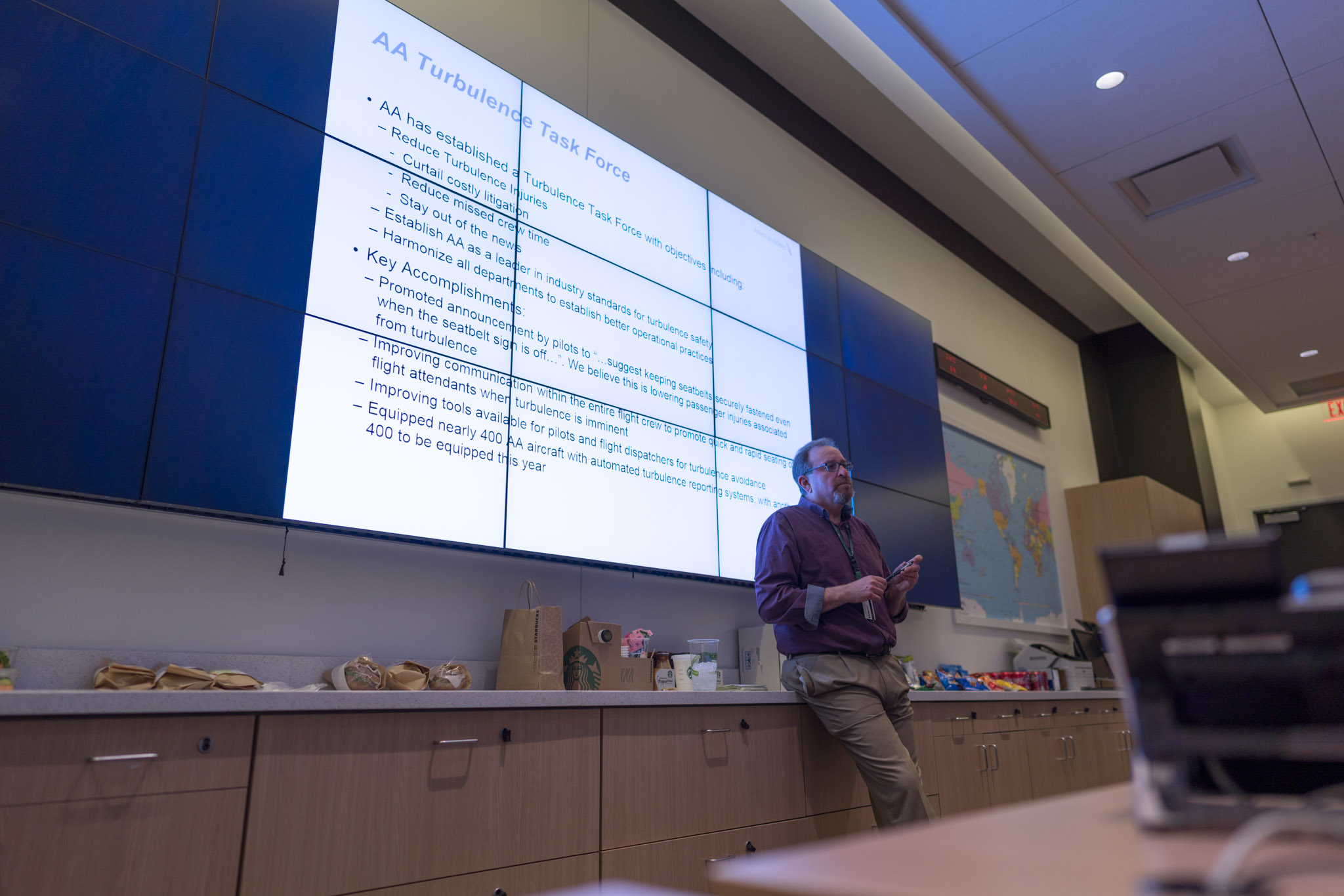

Steve Abelman, program manager IOC weather technology for American Airlines, delivered a wonderfully insightful presentation to us about all things weather: from the 6-hour thunderstorm from the beginning of this article to American’s Turbulence Task Force.

As you can see above, American has nearly 400 aircraft with automated turbulence reporting and will have nearly 800 by the end of 2019. This information, in concert with in-flight reporting tools available to American pilots, appears to be helping reduce turbulence-related incidents.

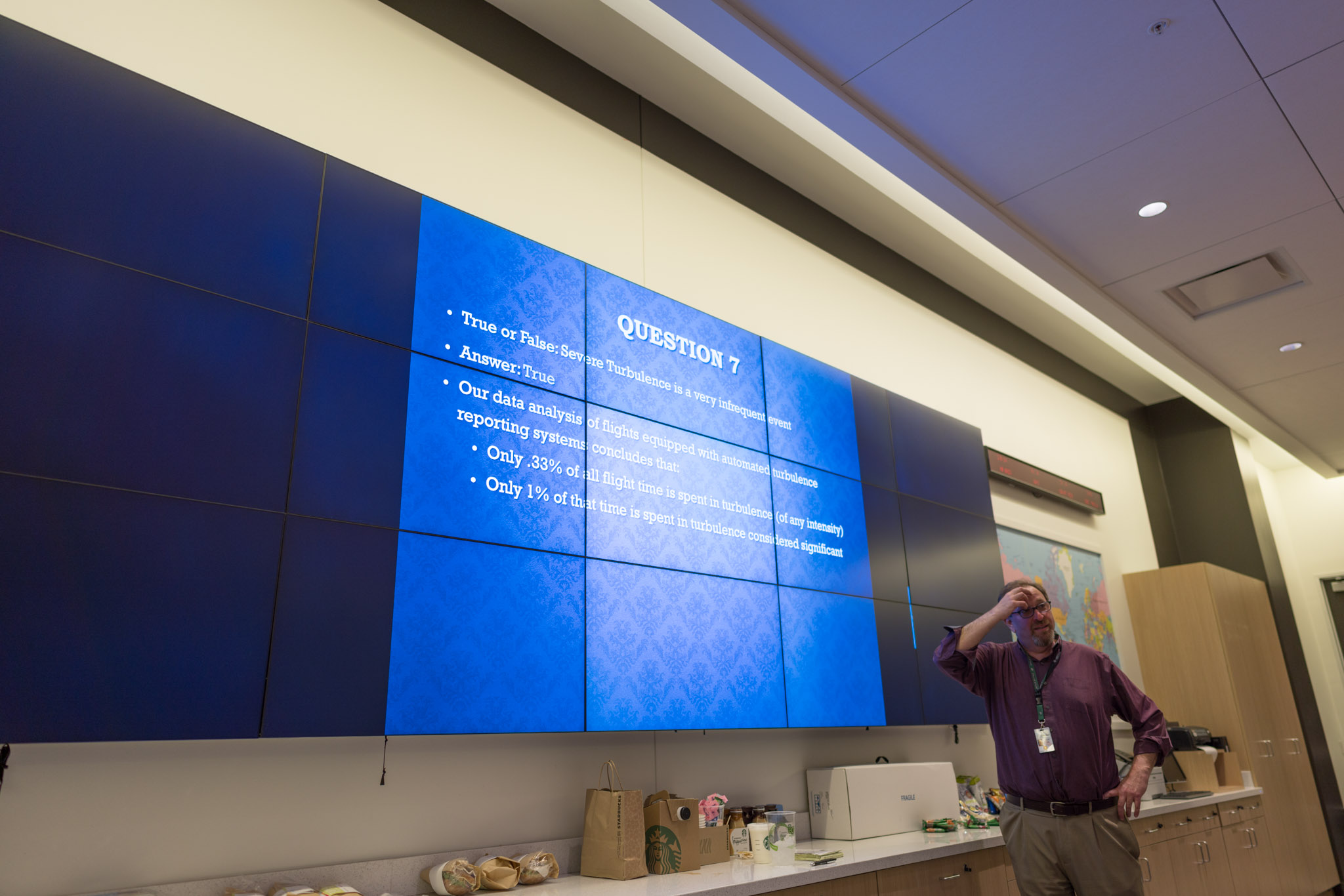

There were two things that really struck me about his presentation: 1) that pilots were encouraged to not leave the fasten seat belt light on the entire flight, and 2) just how rare severe turbulence is.

I’ve flown primarily on American Airlines for years and a consistent frustration is how light-happy some pilots are, and usually once the light is turned back on due to turbulence it just stays on. It desensitizes passengers to the importance of that light, which makes things difficult for flight attendants in the case where passengers really do need to take their seats. I compare that to recent flights on Delta and KLM where, once it was safe to turn off after departure, the light remained off unless needed, and passengers sat the heck down when they saw the light.

In case you can’t read the above, according to Steve’s statistics, out of the thousands of hours in which American Airlines jets are in the air on a daily basis, only .33% of flight time results in turbulence of any reportable sort. Out of that .33%, only 1% qualifies as “severe” turbulence.

Make no mistake, Steve was by no means saying American Airlines had “solved” turbulence, not by any stretch. He updated us on airline industry initiatives to make sharing turbulence data easier and it seems like the industry is finally coming around (led by IATA) on consuming the enormous amount of data generated by airlines. That American is investing money equipping jets with automated turbulence reporting systems was encouraging as well.

American flight academy is a 24-hour teaching center

After a brief test (for fun, and by fun I mean a huge aircraft model from American) where we had to correctly identify airport IATA codes with their cities, and vice versa, we made our way out of the IOC and enjoyed a brisk walk over to American’s flight academy building (the walk was perfectly timed to wake all of us up, it was after midnight at this point). As we approached the building, I saw a man inside stand up, button his jacket, don his cap, and walk outside to greet us. Captain John Dudley, senior manager and A330 fleet captain for American Airilnes, greeted us warmly and professionally, as if it wasn’t a crazy time of night. As we walked into the lobby I saw a cool placard over the doorway and noted, with some irony, how pathetic tired we must have looked walking under the sign.

The building was older and had incredible mid-70’s charm.

As we ogled the American-livery 747, Captain Dudley gave us an orientation about what lied ahead of us that evening. After the orientation he invited us to proceed over to the simulation wing of the building. It was an absolutely massive complex of hallways and staircases, but after a bit of a walk we arrived at a room full of airplane simulators.

(Ok in all truth the picture above was purely taken because the simulators framed the old American logo perfectly and the American flag looked great. Here’s a picture of the actual simulators)

Each simulator was enormous, and this room was just one of many rooms! All told, American has more than 40 flight simulators to train pilots for all manner of flying and ensure they’re prepared for almost any scenario.

Captain Dudley explained that we would be spending some time in the A350 simulator that morning. Seemingly predicting the question we were all about to ask (since American has decided not to take the A350), Captain Dudley, who was actually the first commercial pilot to fly an A350 across the Atlantic Ocean, explained that the simulator was purchased when the model was still in the plans for the airline and will eventually be sold. American has actually allowed other airlines to come in and use it occasionally, since it’s perfectly functional and American no longer has need for it. Captain Dudley invited us into the simulator, an exact recreation of an A350 cockpit.

The detail was immaculate. Every button was exactly the same as you’d see in an A350 cockpit. A computer bank to the port side of the cockpit had a monitor where Captain Dudley, or whoever was responsible for training, could pull up accurate recreations of numerous different airports or create any conceivable flying scenario in the air. With a few clicks of the mouse, he selected DFW Airport and a gate and (it’s hard to emphasize how crazy this was) all of a sudden it truly felt like we were there.

When I say these simulators were detailed, I mean it.

We did not have the full motion capability of the simulator enabled, but even in “non-motion” mode (my name for it) the simulator still gave us the sensation that we were moving. We taxied to a runway and took off.

Captain Dudley explained to us that training takes place all times of day and night and pilots go through extensive and rigorous training, coming back to Dallas for simulator time at regular intervals to ensure their knowledge and skills are as sharp as possible. He then demonstrated to us a few of the safety features of the A350, such as automatic traffic avoidance maneuvering (which was incredible) and the inability for a pilot to put the plane into a position which would damage the aircraft (a pilot could not attempt a barrel roll, for example).

So we could each have a brief simulator experience and get just a glimpse of what pilots go through from a training perspective, Captain Dudley set up a brief 3-mile approach into 17R at DFW. As the various media cycled through it was fun watching each of them experience, however briefly, the joy of being at the controls. I asked Captain Dudley if it ever got old for him, and he said there had never been a day he’d not looked forward to going to work. He was the consummate professional and carried with him an immense amount of pride in the way he performed his duties and represented his airline.

Of course I wanted a chance at the simulator, so I hopped into the left seat when it was my turn, said “my plane,” and got down to business. Proud to say I landed without incident and even managed to look absurdly smug when I handed my camera to someone for a picture of myself.

Brett from CrankyFlier had his turn and Captain Dudley decided it was a good time to simulate some low visibility and bad weather. The control systems were incredible and guided us in for a smooth landing.

I slightly embarrassed myself when, as Brett applied reverse thrusters after touchdown, I braced myself on the ceiling of the simulator so I wouldn’t fall forward (the simulator, as you’ll recall, wasn’t moving…oops). Things were going too smoothly so Brett ran us right over some runway lights as he was bringing us to a stop.

All in all I could not be any more complimentary of Captain John Dudley. He was patient with us, knowledgeable, and again had an immense amount of pride about his airline and the quality of pilots who fly for it. As we were preparing to leave I captured one more picture of Captain Dudley’s hat as we made our way back out into the simulator room.

It was now 4:00am and we were a bit tired

The adrenaline of the simulator waned as we walked through the rest of the simulator rooms (quite a few were in use). We media folks were a bit tired but the corporate communications team and everyone from American were as bright and cheerful as always (ok most of them haha).

Our night was slowly coming to a close. We had but two stops left: American’s maintenance complex at DFW and the Virtual Tower located in Terminal A at DFW Airport.

Tune in for Part III of our series about the American lock-in, coming soon!

Again, when you reproduce text provided by American, you turn your blog into an outlet for AA’s press relations team.

While I do not doubt this was an interesting evening, many of the claims you make here are both unverifiable (“unquantifiable challenges”) and clearly crafted by AA’s press relations team.

Be careful. Your reputation is in the line here. Do you really think you are in a position to comment on AA’s operations center? Are they really doing all they can? How would you know?

Just like this puffed up claims about the use of social media, almost entirely to distract from their elimination of real customer contact channels, these claims about operations are suspiciously self serving for AA and remarkably free of critical review from this blog.

For six and a half years I’ve written every word on this blog (unless I’ve clearly stated it’s a guest post). The same is true of these posts. At no point did American slip any “pre-crafted” phrases to me or suggest I talk about things in a certain way. American did not offer any text for us to “reproduce” about the event, that’s just not how these things work. They sent us the correct spellings of names and corporate titles after the event, that was it.

My reputation is on the line with every word I write and every post I publish, you’re exactly right. And in light of that I still confirm to you that every word of that post was written by me. It was not reviewed or edited by American Airlines either, when I decided the post was ready to publish I simply hit the Publish button.

And yes, the nature of what the IOC handles is unquantifiable. I’m not an operations expert but have at least a decent understanding of how an airline has to work. The decisions made there have far-reaching consequences for the rest of the airline operation, and thus thousands of passengers day to day. Every decision they make is a balancing act based on the cascading impacts it could cause, that’s the “unquantifiable” nature of the challenges they face. I’m not sure if I conveyed that clearly enough in my post but that’s what I was trying to say.

You’re free to believe what you want to believe, and if you think I’m lying to you there’s probably not anything I could ever say to convince you otherwise. American isn’t a perfect airline and I couldn’t disagree more strongly with their Project Oasis or the customer-unfriendly changes they’ve made to the once industry-leading AAdvantage program, which I’ve covered extensively in other posts. I’ve been incredibly critical of American in the past and, should events warrant, have no problem being critical of American in the future.

I’m not quite sure what you’re imagining happened behind the scenes here but the reality is it was me just me sitting here, reviewing the notes from an incredibly full evening, trying to write an authentic retelling of what was said to us and shown to us two weeks ago.

Thanks for your comment and for giving me the chance to state very clearly and proudly that I am the author of every word of this post.

Isn’t it amazing that, purely by chance, authors independently write copy that parrots the press kits of the companies that invite them to events?

Astonishing, really.

I don’t think you’re lying. I think you lack critical self awareness.

You’re welcome to believe whatever you’d like to believe, I received no such “press kit”. You’re accusing me of plagiarism and lying about it, which I take very seriously. What you’re imagining happened is purely that, a product of your imagination.

Check out TPG. They just Bonvoyed away their credibility too.

They gave away their credibility for an invite to the Oscars.

This seems a bit low rent in comparison.

Patrick, good to hear from you. Thanks for making me take time out of my vacation to reply yet again to a comment of yours personally accusing me of lying. Why you continue to feel the need to reply is beyond me.

re: your turbulence part, I haven’t flown AA all that much, but on a round trip MIA-GIG with a lot of low-grade chop, the ‘seat belt’ light stayed on the whole night. As a frequent Delta flier it took me a while to figure out when I might use the lav! There were periods of heavier turbulence, but since the light was already on, one had no way of ascertaining (other than lots of previous flying) when might be best to be un-belted.

The cabin crew pretty much hung out in the galley unsecured, and meal services happened more or less at normal tempo.

Delta longhaul pilots do seem to be good about counting to 20 (minutes, that is) and turning off the light if the initial bumps (or transiting an area reported to have expected turbulence) clear up.

That’s similar to many American flights I’ve been on lately. I hope it gets better quickly!